Each time a new customer walked through the door of the small coffee shop in South Korea where Min-jae shared his story with VOM workers, he hesitated or stopped talking completely. The middle-aged North Korean studied each person’s face anxiously, searching for clues to his or her intent. Min-jae knew from experience that he could never be too careful, even outside North Korea. Spies often cross the border into South Korea to find defectors and report their names to the North Korean government, which then punishes their relatives still living in the country. “In North Korea, no one trusts each other,” said Min-jae, who even suspected his wife of being a spy. “We have to be very cautious about how we think and always careful with our words. I still have that kind of tendency. I get a little nervous, looking back and forth.” With the coffee grinder providing background noise, Min-jae gradually grew more comfortable sharing the story of how he became a Bible smuggler in the most restricted nation on earth. The Bible: Dangerous Cargo in North Korea Min-jae became a believer during a lengthy business trip to China in 2004. While there, he had visited a friend’s

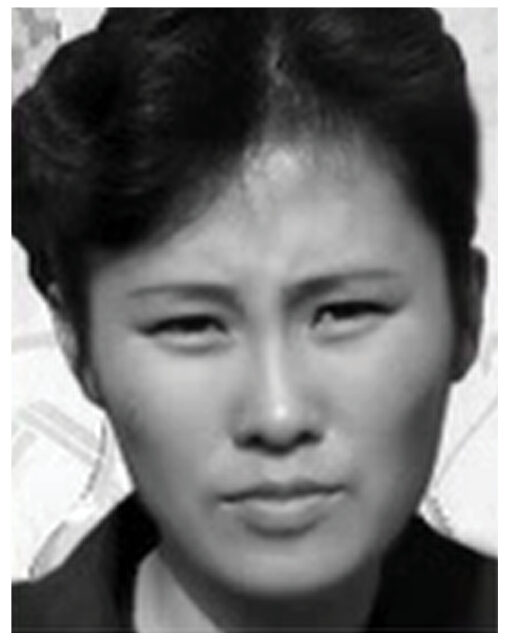

Read MoreIf not for a North Korean government training video, the testimony of Cha Deoksun’s life would never have been known. Produced to train state security agents how to identify and silence those who promote religion inside North Korea, the film denigrates anyone who practices religion. According to the film, Deoksun received Christ in China and then returned to North Korea to share her faith. Incredibly, the propaganda film gives many details about the life of this courageous Christian. It states that during North Korea’s “Great Famine” in the mid-1990s, when an estimated 2.5 million people died, Deoksun was a strong revolutionary whose faith in the government had wavered. After visiting a woman in the northwest to ask for help, she illegally crossed the border into China in search of her uncle. But instead of finding her uncle, who had died, Deoksun found the Seotap Church, where she heard the gospel for the first time. The video says she became a “fanatical believer” who was inspired to return to North Korea and form an underground network of Christians inside the country. When she returned to North Korea, Deoksun apparently turned herself in to authorities for crossing the border illegally. The video

Read MoreAfter spending five years building relationships with 40 North Koreans in China, a faithful Chinese Christian eventually led one man — a North Korean government official — to Jesus. Lee Joon-ki scanned the Chinese coffee shop carefully for the right place to sit. The shop’s owner, a fellow Christian, had told him about a middle-aged laborer from North Korea who was in the shop, and Joon-ki wanted to sit in just the right spot to start a conversation with him. After sitting down at a table near the man, Joon-ki began a casual conversation with him, even managing to draw the coffee-shop owner into the discussion. These conversations, which can quickly turn dangerous for everyone involved, are what he lives for; Joon-ki is a front-line worker who shares the gospel with North Koreans inside China, near the border with North Korea. “Encountering these North Korean people, building relationships and leading them to Christ, is God’s work; it’s full of God’s grace,” he said. “Just meeting with him for an hour is so precious. It is not something we can do normally. Each time could be last time.” Joon-ki, an ordained pastor, has served as a front-line worker for over six

Read Morewatching the church go underground After turning away from Christ in the early days of Kim Il Sung’s Communist regime, a North Korean woman was led back to faith by a single Bible verse. Rhee Soon-ja has vivid memories of her father reading the Bible to her and her six siblings when they were children. She remembers that the verses were printed vertically, rather than horizontally. And although now 82 years old, she can still picture the phrase “Christ Is Lord of This House” hanging from a wall in their home. “My parents prayed that God would use me as His servant,” she said, recalling another childhood memory. “I grew up dreaming of becoming an evangelist.” Those were the days before Korea split into North and South, communist and free. Those were the days when the Christian faith flourished in northern Korea. “There were many Christians,” Soon-ja shared from her living room in South Korea. “I attended the Methodist Church. All the congregations gathered every Sunday.” When Soon-ja was a young girl, her family was among the first to experience persecution under the rule of Kim Il Sung, North Korea’s first leader. Today Christianity is illegal there, and those who

Read Morea dangerous secret Once fearful of even seeing a Bible, a former North Korean border guard now embraces it. Nearly every day for 11 years, Park Chin-Mae dutifully monitored North Korea’s border with China. From 8 a.m. to 10 p.m., he watched for North Koreans attempting to defect or smuggle contraband into the country. Chin-Mae took pride in his work as a border guard, even though he was guilty of the same illegal activities for which he arrested others. Like many North Koreans, he relied on illegal smuggling simply to survive. becoming the enemy When another guard reported Chin-Mae’s smuggling ring, he spent 60 torturous days in prison. And he hadn’t even smuggled the most dangerous item into the country — a Bible. “Those who let Bibles into North Korea had a more severe punishment than someone who kills people,” Chin-Mae said. For Chin-Mae, getting caught smuggling meant being reduced from a respected soldier to a worthless prisoner. For the first 10 days, he was forced to stand in a bowing position and was allowed to move only to use the restroom. If he moved, even during the night, he was beaten mercilessly with a wooden baton. For the next

Read MoreChoon-yei was born into a comfortable and secure family, by North Korean standards. Her father was a military officer, and her mother was a housewife. Since family background largely determines the future for North Korean citizens, her family could expect a good life. In 1995, however, just a few years after Choon-yei’s birth, North Korea experienced the worst famine in its history. Millions died of starvation. And even though her father was a military officer, Choon-yei’s family received only two fistfuls of corn flour each day — not nearly enough to feed a family of four. In desperation, they gave up on the government’s ability to provide for them and began dealing on the black market. But the extra corn flour that her mother had obtained from a relative and sold illegally still barely provided for their family. “Any North Korean who survived that time period is a living miracle,” Choon-yei said. “North Koreans had to break the law just to eat a meal. State security agents would confiscate anything they uncovered on the black market and eat it themselves.” The famine was just the beginning of Choon-yei’s suffering. Her parents died when she was in her early teens, and

Read MoreWhen Pastor Han answered a phone call one afternoon at his church in Changbai, China, near the North Korean border, his wife saw no particular reason for concern. She knew, however, that for several months both Chinese police and South Korean intelligence officers had been warning her husband that he was at the top of a North Korean “hit list.” Pastor Han, his wife and other Christian leaders had even agreed on security precautions designed to protect him while allowing him to continue his ministry to North Koreans. For example, he stopped driving on the border road, he didn’t leave his house or the church alone, and he kept a very strict schedule. But after receiving the phone call that afternoon at church, the pastor uncharacteristically disregarded those precautions and left the church alone. His body was found that evening in a rural area along the North Korean border. North Koreans on the Doorstep Pastor Han Chung-Ryeol and his wife arrived in the Chinese border town of Changbai in 1993. The 26-year-old recent seminary graduate had been called to Changbai to lead a small church of ethnic Korean Chinese, who make up about a quarter of the population in that

Read MoreWhile growing up in North Korea, “Sang-chul” was taught that the concept of God was a dangerous lie. And the government’s zero-tolerance policy toward any suspicion of Christian behavior reinforced the lesson. As the gospel quietly spread in parts of the country, so did a fear among North Koreans that they might be suspected of Christian faith. “We were really afraid of Christianity because anybody could get executed or killed — even if you were looking at the Bible,” Sang-chul said. But in 2013, Sang-chul witnessed the power of a life devoted sacrificially to Jesus: The commitment of a pastor named Han Chung-Ryeol enabled Sang-chul to let go of his fear. Pastor Han was later martyred, on April 30, 2016, because of his bold Christian work. “I really wanted to know why he helped North Koreans, because it was dangerous for Pastor Han to help North Koreans there,” Sang-chul recalled. “Pastor Han unconditionally loved us and treated us well. I felt his heart. The more I met with Pastor Han, I felt more his heart came from the Lord. Without God, he wouldn’t have helped me. That is why I realized Christianity is a true religion.” Like many North Koreans,

Read MoreAs Kyung-ja drifted in and out of consciousness, her head bloodied by repeated blows from a club, she heard her guard shouting words she had never heard in her 56 years of life: “Bible,” “God,” “Jesus.” North Korean Guard: an unlikely Evangelist Kyung-ja understood why the female guard had interrogated her about her latest trip to China and about her daughter’s defection to South Korea, but she couldn’t grasp why she kept asking odd questions about something called Christianity. “I first learned about Christianity from my torturer,” Kyung-ja said. The guard’s confusing and persistent questioning piqued Kyung-ja’s curiosity. At the time of her arrest, she had no belief system or concept of God, but now she had to know what made this Christianity so dangerous. Kyung-ja had been detained twice before for illegally crossing into China. This time, however, was worse. Instead of serving only a few months of “re-education” at a labor camp, she endured repeated torture, most likely because of her daughter’s defection. After brutally beating Kyung-ja for two months, the guard realized she did not have any ties to Christians within North Korea. She then sent Kyung-ja, now a fragile 63 pounds, to a labor camp, and

Read MoreThe young woman settled into her seat in front of a microphone in a closet-sized studio. Hannah skimmed the script, took a breath, and began to read. Once an eager listener on the other side of the broadcast, Hannah is now a familiar voice of forbidden Christian programming that is broadcast into North Korea. When Hannah was a child in North Korea, she spent nearly every night huddled next to the radio with her father. “It was illegal to listen to the radio, but we did it in secret,” Hannah said. Though forbidden, her father managed to purchase one so they could tune in to South Korean radio stations. Even today, the North Korean government attempts to “jam” outside signals and confiscate illegal radios. Citizens caught with one are arrested. Her father was cautious, warning the family to keep their radio a secret. They waited until after midnight, when all the neighbors were asleep, to listen to it. When they did, they heard about a world that was completely different from the one described by their North Korean leaders and by Hannah’s teachers at school. She had a strong relationship with her father, and they often discussed what they heard

Read More